Alcohol

Russia has a renowned and celebrated drinking culture, largely identified with vodka, which at its best reflects centuries of history and tradition, but which at its worst creates a dreadful toll of human and social misery every year. Russian citizens have one of the world’s highest rates of alcohol consumption, and abuse is widespread. The good news is that the situation has not worsened in the past few years, and ongoing changes in legislation combined with social pressures should continue to make Russia’s drinking culture become less extreme.

The state’s attitude towards alcohol, and the damage it causes to its citizens and society, also has a long and torrid history, veering between tolerance and prohibition. Peter the Great, himself a consumer of vodka and a legendary carouser, introduced a licensing system in an attempt to discourage home-brewing, Catherine the Great criminalized sales by non-aristocrats, but the traditions of brewing and drinking were so deep-seated that Russia’s last Tsar, Nicholas II was forced to make alcohol illegal on the brink of Russia’s entry into the Great War in 1914. The Bolsheviks, strapped for cash and looking for new sources of revenue, repealed these laws but only well after the Revolution and Civil War saw them firmly in control. Mikhail Gorbachev, as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, launched an ultimately unsuccessful anti-alcohol campaign in the mid-1980s that saw millions of hectares of Russian vineyards pulled up, from which damage the domestic wine industry is still trying to recover. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, alcohol consumption and dependence increased exponentially with each passing year as the economic certainties of the former system suddenly disappeared, and many people sought to ease the hardships of the cruel new capitalist system by resorting to the temporary oblivion provided by alcohol. By the 1990s, male life expectancy had dropped from the late Soviet level of 65 years to 57 years, a large part of which was attributed to the direct and indirect effects of increased alcoholic abuse. There is probably no better symbol of the country’s desperate situation at this time than the picture of its most prominent alcoholic, President Yeltsin, buffooning his way around the global stage. More recently, Russia’s middle-income status has seen changes to its drinking habits, with vodka consumption down and sales of beer and wines increasing.

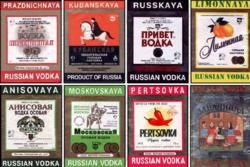

Vodka

Vodka, meaning little water, is the traditional Russian rye-based spirit which has been brewed and enjoyed for centuries, and holds a place within Russian culture and society that is like whisky (or whiskey) to the Scots or Irishman, or sake to the Japanese. Traditionally it was enjoyed with each meal and so a large number of traditions and customs relating to it gradually became common. For Russians, it is not a drink to be mixed or savoured, but should be knocked back in a single gulp, preferably having made a suitable toast to the rest of the table before doing so. An immediate bite of tomato or swig of fruit juice is permitted to help it go down. It also became a cure-all for any sickness or ailment, and to this day if you complain about an oncoming cold or minor aches and pains you’re likely to be advised: «Сто грамм», which translates as "100 grams", the traditional measure of a shot of vodka. There are very many vodka brands available, local and imported, and available at various prices and quality levels. Our advice would be to try a few, find one you like and then stick with it.

Beer

The common attitude towards beer is reflected in a saying: Пиво без водки – деньги на ветер, or drinking beer without vodka is a complete waste of money, the underlying sentiment being that there is no point in drinking beer as drinking vodka will get you drunk much more quickly. In fact, until reforms introduced in 2011 by President Medvedev, beer was not even considered by law an alcoholic beverage and could be sold without restrictions like orange juice or water. As a result, drinking beer in public does not attract the same kind of negative associations it does in other countries, and you will often see groups of people standing around outside convenience stores or metro stations enjoying a beer with friends. In summer especially you will see people swigging beer on the way to and from work, and this is not restricted to the labourer quenching his thirst after a heavy day toiling in the sun – it’s not uncommon to see beautiful young women, office workers and administrators, dressed fashionably and walking daintily from the metro on stilletos, quaffing from a beer on the way into the office. The beer market is one of the largest and most competitive in Europe, and many of the local brands are in fact owned by foreign giants such as Carlsberg, Heineken and SABMiller. Baltika (majority owned by Carlsberg and brewed in 11 breweries across the country) is probably the most famous brand, and is available in 8 different strengths and flavours, including non-alcoholic, pale ale, wheat beer and 8% volume. Local brands include Nevskoye and VP (Vasiliyevskoye pivo). The city has a number of breweries-cum-restaurants which are popular spots to sample a range of beers and enjoy a hearty meal.

Wine

Russia’s wine growing regions are in the far south of the country, in the North Caucasus region which lies between the slopes of the Caucasus and the sub-tropical Black Sea coast. Sovyetskoye champagne was always ubiquitous and can still be found trading under this name (among other brands) at most shops, providing a cheap (about RUB 150) but very drinkable, sparkling wine, the traditional product often quite sweet for western palates but now complimented by brut and demi-brut varieties. The vineyards where it originated, Abrau-Dyurso, were set up by French viticulturalists in the 19th century for the Tsars, and also produce some fine wines under this name. In Soviet days, however, by far the largest amount of wine consumed locally came from the vineyards of the then Soviet republic of Georgia where, it is claimed, wine was invented and has certainly been cultivated and brewed for millenia. Even before the Russia-Georgia clash of 2008, Georgian wine was among the products subject to a trade embargo and therefore no longer available to Russian consumers. In restaurants you will find much imported wine from Europe, Australasia, and the Americas, although the prices are usually quite high. In supermarkets you will find much imported wine too, but it’s worth looking out for Russian wines which share a similar terroir as the Georgian wines but as yet do not have the same international reputation, meaning prices are quite reasonable. And if Georgia was known for its wines, then Armenia was known for its signature brandy Ararat, allegedly one of Winston Churchill’s favourites and still brewed to this day. Similar Russian products trading under the Derbent, Dagestan and Lezginka brands are widely available.

Kvass

Kvass is a lightly fermented and carbonated cold drink based on black rye bread, and typically drunk as refreshment in the summer. You can find it in most supermarkets and kiosks, although traditionally the most common way to enjoy it was to take a few glasses or large bottles to a small mobile kvass tank parked on the street, and buy it straight from the bowser, or tank. Every summer there are news items on television reporting that certain vendors have been arrested for not cleaning their tanks properly. Be aware of this risk, but don’t let it stop you enjoying a traditional Russian refreshment on a hot summer day.

What this means for the visitor is that although not common in the center of a busy city like St Petersburg, extreme public displays of drunkenness are not rare either and may range from the mildly amusing, to the truly shocking and distressing. Certain public holidays, such as graduation day at the end of June, Parachutists’ Day in August, and just about any national holiday are the exception, and caution should be exercised if walking round the streets on these days. Use your judgement, and if possible, avoid any confrontations and try to ignore any drunken approaches or provocations. If you can’t, then seek out the assistance of a local rather than get involved yourself or better yet, find a policeman and encourage him to step in. Fortunately, at least in the larger towns and cities which provide plenty of social and economic opportunities other than getting drunk, younger generations appear to be largely eschewing the kind of relationship with heavy drinking and vodka in particular that their parents and older brothers and sisters enjoyed, and are as likely to be found ordering cappuccinos or a kalian at a bar as a round of vodkas.